I was browsing the local library, and I went into the adult non-fiction section. They had a section of books about music and musicians, and some of these books were memoirs that musicians have written about their personal lives and their careers. To be honest, I didn’t grow up listening to a lot of old-school rap music. Whenever I would listen to hip-hop on iTunes, I would want to listen to the clean versions that did not have any swearing because I thought swearing was bad and I didn’t want to repeat the explicit language on the album. When I was in my orchestra class in sixth grade, there was this Black kid named Christopher Weaver and he was showing his friend, a Black kid named Austin Stevens, a music CD disc. The disc cover had an African American baby on it just sitting there against a white background. In the right corner there was this sticker that read in big capital letters: PARENTAL ADVISORY, EXPLICIT CONTENT. I was so religious about avoiding CDs that had that big old black and white sticker on them that I was rather taken aback when I saw that Christopher had that CD in his hand.

“What’s that?” Austin asked him.

“A bad CD,” Christopher told him.

I remembered reading in a music CDs catalog around that time (I think it was either Best Buy or Fry’s Electronics. I cannot remember) and they were selling various music CDs. A few of them included Follow the Leader by the rock band Korn, which shows a bunch of children playing hopscotch as a little girl runs towards the edge of a cliff and proceeds to jump off of the cliff. There was another Korn CD called See You on the Other Side that had a disturbing-looking album cover of this pale frightened boy holding a decapitated teddy bear staring out as a rabbit places a crown on him and as a horse holds the decapitated teddy bear’s head. And then I saw an album in the catalog of an African American baby sitting in this empty white void, and the title was Ready to Die. At first, I thought that Ready to Die was a heavy metal rock album similar to Korn’s music. But then I finally reached my 20s and realized that Ready to Die was a hip-hop album by the late and great Christopher Wallace, also known as The Notorious B.I.G., also known as Biggie Smalls, and also known as just Biggie. Like I said, I did not grow up listening to a lot of old school hip-hop. The only times I would hear hip-hop was from school dances or kids rapping the lyrics. If I did hear rap music on the radio, it was always censored. I grew up with Soulja Boy, T-Pain, and Ludacris. I did not grow up listening to The Notorious B.I.G., Tupac and other 1990s rappers until I was older. During my sophomore year of college, I enrolled in a course called Introduction to Black Culture by a really sweet man named Kevin Quashie. The course was an introductory class in the Afro-American Studies department (they changed the name to Africana Studies around my junior or senior year) and we watched movies such as Spike Lee’s Bamboozled and studied artworks by African American painters in the 20th century. We also read a graphic and disturbing excerpt from a non-fiction book about the lynching of African Americans during the 1900s. One of the parts of the course I remember, though, was the unit on hip-hop and rap music. In class one day we listened to songs like “Lose Control” by Missy Elliott and “We Don’t Need It” by Lil’ Kim and Lil’ Cease and also studied the origins of hip-hop and pioneers of hip-hop like Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. After the course, I started exploring more hip-hop records out of curiosity. As I have gotten older, I have gained a deeper appreciation for hip-hop music that came out in the 1990s and 2000s. Hip-hop is part of my African American heritage and it has provided solace and inspiration for a lot of young people. I consider Tupac and Biggie Smalls to be poets and even though the lyrics of the music are misogynistic and homophobic, I have to remember that at the time that these artists were rapping, there was a lot of anti-gay sentiment and the AIDS crisis in the 1980s disproportionately impacted LGBTQ people, causing them to face scapegoating and ostracism from American society. Hip-hop emerged during the 1970s and 1980s so it coincided with the sexual revolution and the AIDS crisis. Art is a product of what is going on in society, and while artists have used their music to speak to racial discrimination and injustice, they have also used their music to speak negatively about groups that they perceive to be a threat. This also comes from a lack of education about the LGBTQ community because unlike now, where we have social media and online resources that non-profits such as The Trevor Project and The Human Rights Campaign have provided for people, people lacked the education and resources to meet the LGBTQ community where they were at and provide them with the support and resources that they needed. It does not in any way justify the use of bigoted language such as the F word and the D word, but looking at the use of homophobic slurs in hip-hop from the context of history helped me understand why rappers use this kind of pejorative language in their music.

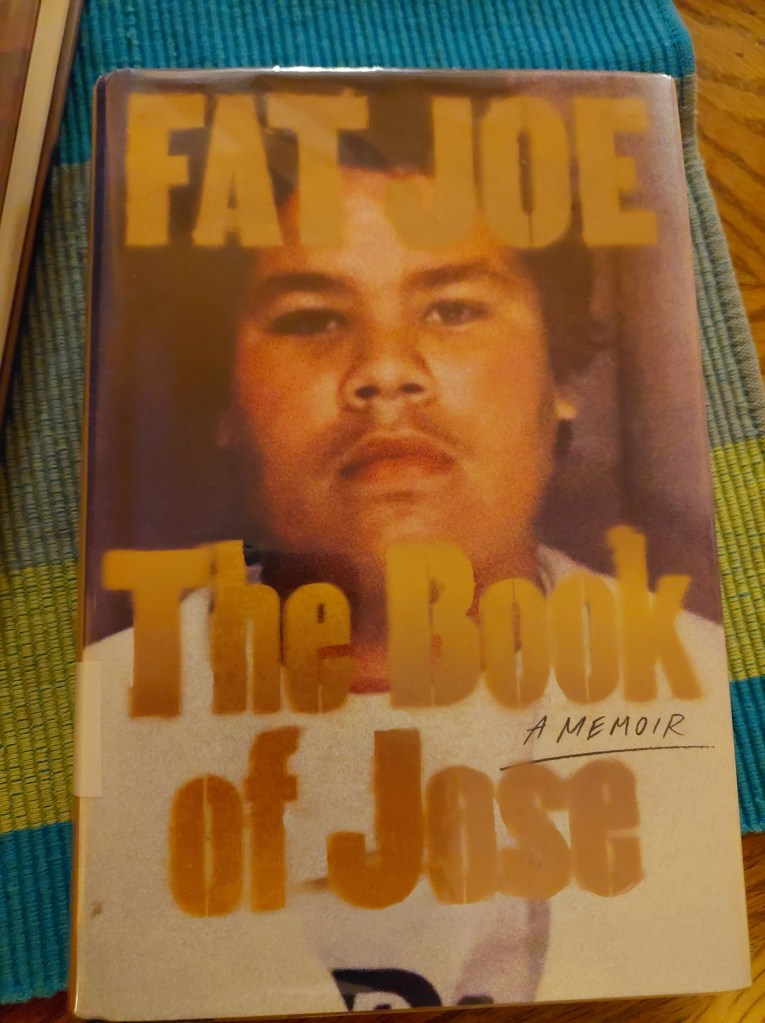

I knew about Fat Joe when I was younger, but because I didn’t like songs with explicit language (I was worried about repeating it), I listened to the clean version of “Lean Back” by Terror Squad. When I finally got over my days as a language prude, I decided to pop in some rap music and listen to the full explicit lyrics. Recently, after getting Spotify Premium, I listened to full albums, and some of these albums were hip-hop albums. As I read The Book of Jose, I became curious about Fat Joe’s music. There was an album of his that came out in 2005 called All or Nothing, but I never listened to it. A month ago, I listened to it on Spotify and really love the flow of Fat Joe’s rhymes. As a queer person, I did wince each time I heard him use slurs like the F-slur, but I did my best to listen to as much of the album as I could.

There was a lot about Fat Joe’s history that I didn’t know about. He was born and raised in the Bronx in New York City and he grew up in poverty and around a lot of gun violence. What saved him was hip-hop music. He started to collaborate with other rappers and put himself out there and eventually he became a number one-selling hip-hop artist. He not only discusses his career, but he talks about meeting his wife, his children and his family. It was sad to read about the death of his friend and fellow rapper, Big Pun. To be honest, reading this book reminded me of this piece of writing that was published in the 1200s called “The Eight Winds.” It is by a Japanese Buddhist reformer named Nichiren Daishonin and it discusses how important it is to not let external influences like fame, criticism, suffering and pleasure, cause Buddhist practitioners to lose faith in their Buddhist practice. Practicing Buddhism reminds me time and again that even if I achieve fame or success in my music career, I cannot let it get to my head. Also, I need to give back to my community because that is the best way to express my gratitude for all of the wonderful music education and opportunities that I received growing up. I also need to be true to myself and not think that I am better than people just because I have trained for so long as a classical musician. The minute I act like my shit doesn’t stink, it’s over. I’m fucked.